by Erin Doane, senior curator

The Knox Hat Company of New York City produced

fine hats for nearly 100 years. Before his speech at the Cooper Institute in

1860, Abraham Lincoln purchased a new Knox stovepipe hat. He was one of 23 U.S.

presidents who wore the company’s hats. But you didn’t have to be elected to

the highest office in the country to wear a hat made by the Knox company.

Regular people could purchase a Knox hat right here in Elmira. CCHS has seven

of them in our collection, four of which have labels from local stores.

.JPG) |

| Knox

label inside a fedora sold by Burt’s, Inc. in Elmira |

First, a brief history of the Knox Hat Company.

Charles Knox, an immigrant, founded his company in lower Manhattan in 1838. At

first, he sold beaver hats out of a small shop, but the business quickly grew.

His son Edward, a Civil War veteran, took over in 1878. By the turn of the

century, Knox hats were being sold all over the country, and the company’s

factory was one of the largest in the world. Edward died in 1916, but the

company continued until 1932 when it merged with Cavanagh-Dobbs, Inc. and

Dunlap & Company to form the Hat Corporation of America. Hats were still

being produced under the Knox brand name until the early 1980s.

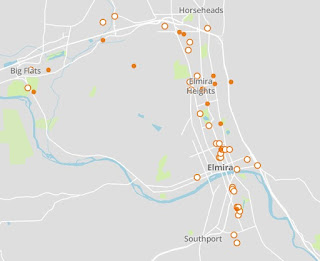

The Knox Hat Company put a large portion of its

budget into advertising and had thousands of sales agents throughout the

country. One could purchase Knox hats in Elmira from the late 1890s through the

1970s.

|

Advertisement for Knox hats at Callahan’s,

106 West Water Street, Star-Gazette,

May 14, 1898 |

H.

Strauss

.JPG) |

| Knox Hat Co. derby sold by H. Strauss, early 1900s |

.JPG) |

| Label inside the derby |

H. Strauss was the sole agent of Knox hats for men

in Elmira from the early 1900s through the 1920s. Herman Strauss, founder of

the company, came to the U.S. from Baden, Germany in 1863 when he was 17 years

old. He started as a peddler, carrying a 120-pound pack door-to-door. In 1872,

he opened a haberdashery at 205 East Water Street. He sold men’s clothing and

accessories at that location for 59 years and was active in the business until

just a week before his death on March 23, 1932 at the age of 87.

|

|

H. Strauss advertisement, Star-Gazette, August 23, 1912 |

Herman’s son Charles W. Strauss took over the

business in 1932. The store was closed briefly to settle the estate but

reopened after renovations in September of that year with all new stock. In

1937, the shop moved to North Main Street after 65 years in the same location.

It was forced to close after the flood of 1972. At that time, Charles’s nephew

Harold Unger was leading the company, and had been doing so since Charles’s

death in 1964. Rather than reopening downtown, H. Strauss opened a new store at

the mall. That lasted until 1991 when Bruce R. Chalmers, who had worked at H.

Strauss under Unger and purchased the company in 1985, moved the store back to

Elmira. He set up shop at 311 College Avenue. In 1994, H. Strauss relocated to

636 West Church Street and it remains there today, though it is currently only

open by appointment.

Burt’s

Inc.

.JPG) |

| “Foxhound”

style Knox fedora sold by Burt’s Inc., 1953 |

.JPG) |

| Burt’s

label inside fedora |

By the 1930s, H. Strauss was no longer the sole

agent of Knox hats in Elmira. They could also be purchased at Burke O’Connor

Men’s shop in the Mark Twain Hotel. The primary seller of Knox hats by the

mid-1940s, however, was Burt’s Inc. at 157 North Main Street.

|

| Advertisement

for H. Strauss, Star-Gazette, May 28, 1945 |

0Arthur H. Burt and Walter Daily received an

official charter for Burt’s, Inc. from the New York State Department in 1922.

Burt was born and raised in Elmira and Daily came here in 1917. That year, the

pair established Burt’s Inc. to sell men’s and boy’s clothes. Their first store

was at 113 West Water Street. In 1922, they purchased the clothing store of

Fred J. Bernet at 103 Water Street and began conducting business there. Burt

continued to run the business when Daily left in 1935. The store moved again in

1937 to 157 North Main Street. It remained there until 1963 when Burt passed

away and the store closed.

|

| Burt’s

Inc. advertisement, Star-Gazette, November

2, 1944 |

Burt’s Inc. started selling Knox hats in the later

1920s and continued selling them through the store’s final closing in 1963.

Jerome’s at 350 North Main Street took over sales of Knox hats after Burt’s

closing and continued selling them through 1979.

Mrs.

G.W. Cornish and The Cornish Shop

.JPG) |

| Ladies’

Knox hat sold by Mr. G.W. Cornish, c. 1910 |

.JPG) |

| Label inside the hat |

The Knox company did not only make hats for men.

They also produced women’s hats. In 1906, Mrs. Gene W. Cornish began her

millinery business at 111 West Market Street, offering a fine line of trimmed

and untrimmed hats. She traveled regularly to New York City to purchase new

merchandise - including Knox hats - and to visit family.

|

| Advertisement

for Mrs. G.W. Cornish, Star-Gazette,

September 28, 1906 |

The change in the business name to the Cornish

Shop first appears in the local newspaper in 1914. That year, the store also

relocated to 108 North Main Street. It continued to be the purveyor of Knox

hats, offering the latest seasonal styles for fashionable women.

|

| The

Cornish Shop advertisement, Star-Gazette,

October 13, 1919 |

Fourteen years later, in 1928, the Cornish Shop

moved into one of the storefronts in the Mark Twain Hotel where it continued to

carry Knox hats. It’s interesting to note that in the 1930s, S.F. Iszards, the

Mark Twain Hotel’s neighbor just down North Main Street, also sold Knox hats.

.JPG) |

| The

Knox “Midshipman” sold by The Cornish Shop, 1920s |

.jpg) |

| Labels

inside the “Midshipman” |

The Cornish shop remained at the Mark Twain Hotel

until 1936. It moved to a couple other locations downtown over the next few

years and was located at 107 W. Church Street in 1942 when its proprietor

passed away after an extended illness. Gene Cornish’s passing marked the end of

the Cornish Shop but one of her long-time employees, Blanch K. Holland, took

over the store, renamed it the Holland Hat Shop, and continued selling Knox

hats there through the middle of the 1940s.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)