By Kelli Huggins, Education Coordinator

When we talk about Rorick’s Glen, we mostly remember it for

its amusement rides, theater that hosted the Manhattan Opera Company every

summer, and its connections to the trolley lines (having been founded to give

people an excuse to ride more often). My favorite story about Rorick’s Glen,

however, is about the donkeys.

In June 1902, W. Charles Smith brought 12 Angora goats and a

few donkeys to Rorick’s Glen. The management intended to have them pull carts

carrying visitors over the park’s new walking trails. The animals were

outfitted with little yellow and red carts and the paying public were invited

to take a ride. There was one problem: no one seemed to have anticipated just

how stubborn goats and donkeys are. On what was supposed to be the inaugural

run, not a single animal would move. The animals were whipped and still would

not budge. Customers watching on suggested a gentler method, and that too

failed. Customers were refunded their money and the stables were shut down for

business until they could “teach the animals how to walk.” Smith was

particularly upset since the man he purchased them from claimed they were “high

steppers and willing workers.”

|

| Rorick's trail showing a donkey and a goat hitched to a cart, c. 1902. |

A month later, Smith and his assistants were reportedly

making progress and the animals were now demonstrating “agility and submission." The

animals, now “acting for all the world like park donkeys and goats should act,”

took passengers around the paths at the Glen. The animals lived in a small

cabin that was converted into a makeshift stable on the side of the hill.

It’s unclear how long these donkeys and goats were employed

at Rorick’s. In 1910, however, new donkeys were brought in. Possibly the first

donkeys and goats had died, or perhaps they were only ever used for that 1902

season. Either way, on June 1, 1910, Colorado cowboy George “Blinky” James

arrived via train in Elmira with a new shipment of donkeys. The donkeys came

with fantastical, most likely totally invented, back stories. Hailing from the

Ratoon Mountains of the Rockies, the donkeys were reportedly descended from the

mules of Cortez’s Spanish Army which conquered the Aztecs. One of the donkeys

was also said to have made its original owner’s family rich by discovering a

gold mine by kicking dirt. The owner died on that expedition before the discovery

and a court supposedly granted 1/3 of the profits to the deceased’s family

because the burro was the discoverer.

|

| Some of the Colorado donkeys, 1910 |

Blinky James left Colorado with 20 donkeys and arrived in

Elmira with 21. Somewhere on the train between Chicago and Elmira, a donkey was

born. Upon arrival in Elmira, this made for an instant marketing campaign. The

Elmira Water, Light & Railroad Company, owners of the donkeys and the Glen,

partnered with the Star-Gazette to hold

a contest for children to name the new foal. Helen Turnbull of 514 Lake Street had her submission

selected and the donkey was named Roricka. Helen won a free pass to ride the

burros until the 4th of July. Helen wrote “I think Roricka

(Ro-ree-ka) would be a pretty name.” Other names suggested included: Nobino,

Jacko, Cute, Teddy, Comet, Sanco Pansy, Free-n-Equal, and Billy Bunco.

These donkeys, likely due to their training by Blinky and

his staff, seemed to adjust better to their tasks than the 1902 donkeys and

goats. They did however suffer some effects of the change in climate and

elevation from the Rockies to the Southern Tier. Some were off duty for a

couple of weeks before recovering or acclimating.

By July 1910, the newspapers were proclaiming that the

donkeys were a must-see for everyone. One article said: “Moonlight burro parties

have become all the rage at Rorick’s Glen. The sport is being enjoyed every

evening by Elmirans who have tired of the usual forms of entertainment and are

looking for something out of the ordinary.”

|

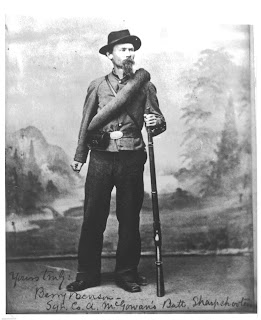

| Burro party, 1910. Blinky James is front and center. From newspaper on Fultonhistory.com |

Another proclaimed: “Had the officials of the Elmira Water,

Light & Railroad Company dreamed how popular the little burros at Rorick’s

Glen were to become, doubtless they would have purchased a greater number….They

are kept busy nearly every hour of the day carrying the children about the

pretty Glen upon their backs.”

A July 24, 1910 article discussed the donkey-riding

experience of prima donna Mrs. Horace Wright, better known by her stage name

Rene Dietrich. She exclaimed, “Well, this burro ride has climbing Pike’s peak

or a ramble in the Alps crowded right off the map.” Along with Blinky, Mrs.

Wright and her husband decided that they wanted to off-road it, after already

riding the short and long trails. The group went from Rorick’s across the

Rorick’s bridge (the burros were not happy about that and “one burro was partly

carried and partly shoved” across). They then went east down Water Street

before going back to Fitch’s Bridge. Another donkey had to be carried over the

bridge so the others would follow. When they got back to the paths on the hill,

Mr. Wright’s burro sat down and was forced up with a fence rail. Mrs. Wright’s

burro tried to jump over a barricade, and since “a burro can’t jump any more

than a camel,” she was thrown off. The donkey remained halfway over the fence,

“prepared to stay there indefinitely” until more “shoving and heaving” got it

to move.

Of the trip, Blinky said “Cute little things, them burros.

Never run away or go fast. Patient little things, they’re well trained.”

“They’re well trained all right, not to exceed any speed limit,” said Mr.

Wright, “you’re wise to charge by the hour, and not by the mile.” The Wrights were so enamored

with the donkey riding that they came back every day. Baby Roricka was

also rubbing elbows and hooves with the opera company stars; she was brought on

stage for “Family Affairs,” a farce at the theater.

|

| The Wrights enjoying their donkey riding |

Blinky James' authentic cowboy charm proved very popular with visitors …perhaps even too popular. From September to November

1910, the divorce proceedings of Fred M. Schmidt and Minnie Kinner Schmidt were

published in the local newspapers. Mr. Schmidt filed for divorce from his wife

alleging that she had abandoned him and had been having extramarital affairs.

Mr. Schmidt claimed that Mrs. Schmidt has spent the night at the Lackawanna

Hotel with Blinky on September 8. Then

on September 10, she allegedly stayed at the hotel with Arthur Parker, a

one-armed burro assistant. She admitted guilt of adultery and was sent to the Albion home

for wayward girls. Blinky James denied any involvement in the Schmidt affair.

By the end of November 1910, Blinky James headed back to Padroni,

Colorado. Reportedly, “eastern life was not for George James.” It was the end

of the season and there was no mention of him leaving because of the adultery

scandal. There were reports that he would come back the next season, but it

seems that he may have left Elmira for good.

The donkeys wintered at the Maple Avenue Park, but were back

in action in 1911, ready to carry “youngsters over the picturesque paths

through the glen, from the theater to the top of the Indian Steps.” That June a

new ½-mile burro path opened. In the off-season of January 1913 the highly-decorated

donkeys marched in the parade for the opening of the F.C. Lewis company.

In April 1913, four new burros added and it was noted that

these “long-eared hill climbers” were “as frisky as kittens and as comical as

monkies [sic].” While they weren’t yet ready to ride, children would be able to

come and see them.

The donkeys were so popular they became fodder for cultural

commentary. A joke in the news used the donkeys to take a jab at suffragettes:

“Brownie, Rorick’s glen burro, carried a 250-pound suffragette around the long

trail. Brownie is now known as the suffering yet burro.”

The donkeys remained popular for the next several years. The

E.W.L.&R.R. Co. gave away a baby burro to the person who correctly guessed

the number of people coming into the Utilities Company booth at the Elmira

Industrial Exposition. It seems like a strange and high-maintenance prize, but

suggests the continued popularity of the donkeys.

The last reference I’ve seen to the donkeys was from September

1917 when a donkey escaped from the Glen and was found by Patrolman John

Drolesky. While he “was phoning to headquarters, the animal became overly

affectionate and proceeded to butt him in the stern.”