By Rachel Dworkin

As a kid, I loved trick-or-treating. Who doesn’t love costumes and free candy? Most Americans agree with me. In 2022, there were 40.9 million trick-or-treaters between the ages of 5 and 14. Americans spent $3.1 billion on candy for them. I know I certainly spent my share. The tradition loomed so large in my childhood, it’s hard to believe it’s barely 100 years old.

In Europe, people have been dressing up in costume and visiting homes for food around Halloween since at least the 15th century. Despite the tradition being wide-spread across the British Isles, it wasn’t until the 1910s that it caught on in the Americas. Prior to that, Halloween, if it was celebrated at all, was marked by private parties, public dances, and petty acts of vandalism. The first record of costumed children going door-to-door in North America is from a newspaper account in Kingston, Ontario, Canada in 1910. It was described in a Boston suburb in 1919 and Chicago in 1920. The phrase “Trick-or-treat” also originates from Canada and appeared in the 1920s. The phrase wasn’t used in the United States until 1932 and wasn’t widespread until around 1940. The practice as a whole didn’t really catch on across the country until the 1950s.

|

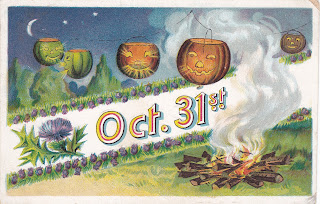

| Halloween postcard, ca. 1910s |

It’s hard to say when trick-or-treating came to Elmira and Chemung County. None of the diaries we have from the 1910s or 1920s mention it, nor do the newspapers. Halloween parties and dances were common, as was trouble-making. Throughout the 1930s, Police Officer James Hennessey describes combating roving Halloween gangs of teenage boys who smashed windows and set fires throughout the last weeks of October. In 1934, the Elmira Heights Police Department issued a warning in the newspaper promising to crack down on holiday mischief-makers. Hendy Avenue School began holding an annual costume party and bonfire to keep kids off the streets.

|

| Halloween postcard, ca. 1910s |

The first mention of kids asking for treats in Elmira appears on October 28, 1939 when columnist Matt Richardson railed against kids these days saying:

“The youth of today doesn’t wait until October 31, the eve of All Saints' Day or Halloween, to celebrate. It lays aside a week for it, but not with tick-tack, jack-o’-lantern, and purse-tied-to-a-string capers. Instead the boys of today walk right up to neighbors’ homes boldly, ringing the doorbell and inquire: “Have you got a hand-out for us?”

1942 was the first time I found the practice of trick-or-treating mentioned in a local diary, although not by name. Jennie L. Hall of Elmira, wrote “Had nineteen here for Halloween handouts. Glad to do it.” She wrote about it again in 1945, 1946, and 1947, mentioning children coming to her door and her own grandchildren going around to the neighbors.

It had certainly caught on here by 1948. That was the first year the phrase trick-or-treat appeared in an Elmira paper. It was also the first year Ira Heyward ever participated. In an oral history in 2013, he described his first Halloween in Elmira after moving here from rural South Carolina:

“I remember the Charrons who lived kitty-corner from us on Washington Street. They took me one time, my very first year here, Halloween-ing and I had never done that before. So, what happened was, I got back home and I had all this candy and stuff. My mom thought I had robbed somebody or went down to Cary’s and ripped them off. It was a little candy store about two blocks from our house where they sold penny candy. And my mother was very upset about that because she thought I had stolen it. But it wasn’t. We had gone house to house, pretty much what the kids do today. So, she took me across the street to Mrs. Charron and she explained to mom that no, we kids do this every year. And the kids go out and collect candies and come back and eat it.”

Over time, Halloween trick-or-treating has changed. While fruits, nuts, and homemade cookies were once common treats, people these days prefer prepackaged candies. In the late 1960s, there were widespread reports of people inserting razors, pins, or drugs into homemade treats. In 1969, an unnamed Elmira woman reported finding one in a cookie. The newspapers advised parents to check over their children’s hauls. Mine certainly did when I was growing up. According to surveys, 88% of parents do. Since 1950, children have also been collecting money for the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). What started as a one-time fundraiser in Bridesburg, Pennsylvania quickly became a movement. In 1953, trick-or-treaters from the Westminster Fellowship of Horseheads Presbyterian Church raise $77.75. By 1960, 3 million American kids across 11,000 communities raised $1.75 million.

|

| Robot costume, 1966. Image courtesy of Elmira Star-Gazette. |

The Elmira Heights Police Department first began setting trick-or-treating hours in 1962. The City of Elmira followed suit in 1971, although not without some push-back. This year, trick-or-treating is scheduled to run from 5-8pm in the Town of Catlin, 5:30-8pm to in the City of Elmira, and 6-8pm in the Village of Elmira Heights. Make sure to have plenty of candy ready to go.

Note: In the course of writing this blog, I realized that we don’t have any trick-or-treating photos. If you have some you’d like to share, please consider donating.