by Susan Zehnder, Education Director

For the past thirteen years, the Chemung County Historical Society has joined forces with the talented Elmira Little Theatre and Friends of

Woodlawn Cemetery to present an historic Ghost Walk along the paths of Woodlawn

Cemetery. Unlike the artifacts and documents we have at the museum, at Woodlawn

Cemetery, we’re sharing stories of people who lived their lives in the area.

The stories range from heartwarming to hilarious and deserve not to be

forgotten.

October is a natural time of year to honor those

who have passed on. Summer feels like it's coming to an end. Falling leaves and colder temperatures suggest winter is

on its way. Plans however for our annual historic Ghost Walk actually start back

in the summer. In July we start to research, write, and revise original scripts

based on the lives of potential characters. We visit the cemetery to find the

perfect combination of characters and walk various potential routes. Ghosts are

selected on variables like a mix of genders, ages and professions. We balance the mood of the stories we share. And, we pay attention to grave site locations. Ghosts

must be close enough to get to on a reasonable walking tour, and far enough

apart that when each actor tells his or her story, it won’t disturb the others.

Final scripts are passed on to Elmira Little Theatre members who

audition, cast and bring the ghost stories to life. As we get closer to the walk

date, Friends of Woodlawn Cemetery provide people to carefully guide each

visiting group along the paths to meet the ghosts. Other people are

involved including those who keep the lanterns lit, drive the buses, welcome

visitors, count bus riders, help with gathering tickets, run the trivia contest

and jump in to fill in where needed to keep things going.

Many people who are part of this event have their own stories to tell. Quite a few volunteers have been doing this for years, including those who have participated as long as the event has been going on. Among them are a brother and sister who stepped in and became guides to honor their father when he wasn't able to do it anymore. Another guide drove from Ithaca to participate after falling in love with the event that her sister volunteers for, and this year a guide was surprised to hear a ghost story involving an act of kindness her own grandfather did. All the people who are part of this event are so important to its success and we can't thank them enough.

Many people who are part of this event have their own stories to tell. Quite a few volunteers have been doing this for years, including those who have participated as long as the event has been going on. Among them are a brother and sister who stepped in and became guides to honor their father when he wasn't able to do it anymore. Another guide drove from Ithaca to participate after falling in love with the event that her sister volunteers for, and this year a guide was surprised to hear a ghost story involving an act of kindness her own grandfather did. All the people who are part of this event are so important to its success and we can't thank them enough.

|

| Lanterns being checked and ready |

In thirteen years, the historic Ghost Walk has changed. In the beginning, there were three ghosts and four tours that took place during one evening. Now the event lasts two nights, and involves four or more ghosts with eight tours each evening. It brings 400 visitors to the museum and to the cemetery, and with only five full-time staff, it takes a heroic effort, and many volunteers to pull this off. This year we were rewarded by selling out all 400 tickets in just two weeks. Our event at the graveyard is to share some stories of those who are buried there, and we are thrilled that history can still be so exciting and popular. We also encourage anyone who missed getting tickets this year to watch for notices next September.

|

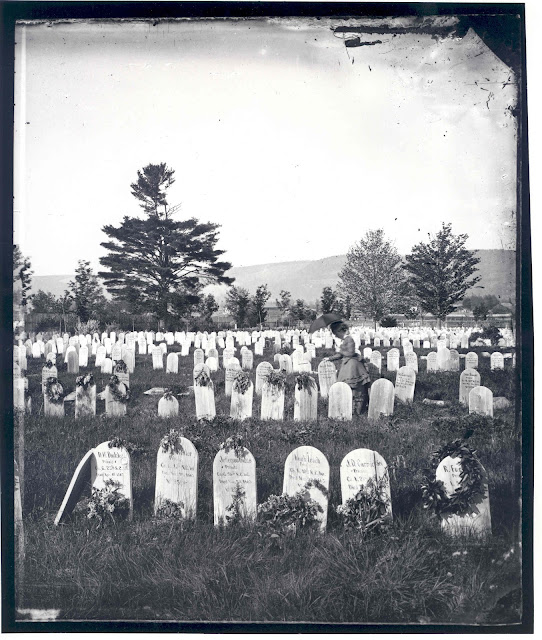

| Woodlawn Cemetery |

The historic Ghost Walk for this year is over, and the 2019 ghosts have been revealed. These scripts are now posted on our CCHS website.

This year, also look for an additional event coming up. Concerned that our ghost walk isn’t accessible to all visitors, especially those unable to walk the ¾ mile trek at night, on October 30th we are hosting another event called Ghostly Readings. At the museum on that Wednesday from 1:30 pm-2:30 pm, staff members will read this year’s ghost scripts and share images of the people we’ve profiled. We will also feature a mystery celebrity reader. Tickets for this event are $5 and include admission to the museum, cider and donuts. We encourage you to call to make reservations, and hope to see you here or in a year when we do this all again!

|

| Call us at 607-734-4167 for reservations or email educator@chemungvalleymuseum.org |