by Erin Doane, Senior Curator

On May 7, 1909, 225 boys descended upon East Hill overlooking Elmira. Over the course of the morning, they planted some 3,000 pine and spruce trees at Quarry Farm. The Star-Gazette called it the most substantial observance of Arbor Day ever conducted in this city.

Susan Crane and the corps of tree planting boys at Quarry

Farm

Arbor Day was the brainchild of J. Sterling Morton, a newspaper editor in Nebraska City, Nebraska and secretary of the Nebraska Territory. In 1872, at a meeting of the State Board of Agriculture, he proposed a tree planting holiday to be called Arbor Day. The first celebration took place on April 10, 1872 and more than 1 million trees were planted in Nebraska that day. Arbor Day became a legal state holiday in Nebraska in 1885 and by 1920 more than 45 states and territories celebrated. Today, National Arbor Day is celebrated in all 50 states. The most common date for observance is the last Friday in April, but some states pick a different date for when the weather is best locally to plant trees.

The tradition of planting trees on Arbor Day became widespread in school in 1882. In 1909, trees were planted in school yards throughout Elmira and Chemung County. A group of over 200 boys chosen from the seventh and eighth grades of the local grammar schools was also invited to participate in tree planting on three acres of land set aside by Susan Crane at Quarry Farm. It was the first time this type of reforestation project had been done in Chemung County.

|

| Students planting trees at Quarry Farm, 1910s |

Dr. Arthur Booth, president of the Chemung County Forest, Fish and Game Protective Association, led the project. The Association purchased 4-year-old saplings from the New York State Nursery in Saranac Lake and had furrows plowed to the right depth so that everything was ready when the boys arrived. Susan Crane planted the first tree and Rev. S.E. Eastman planted the second. Then the boys went to work. One boy deposited moist earth and water on the spot where the tree was to be planted. The next boy placed a young tree in position. Then a third boy tamped the earth down around the seedlings. This efficient method allowed the boys to plant 3,000 trees by lunchtime.

Statistics at the time showed that a large percentage of trees planted by school children on Arbor Day died fairly quickly. Youngsters and their supervising adults either failed to plant the saplings properly in the first place or neglected them after they were in the ground. Following the May 1909 tree planting at Quarry Farm, a drought hit the region. Many were concerned that the new seedlings would not survive. That summer, a state forestry inspector went to Quarry Farm. He discovered that the percentage of trees living from the Arbor Day planting was even higher than that of the trees planted in the Adirondacks by trained forestry men. Of the thousands of trees planted at Quarry Farm, the loss was only 8 percent.

|

| Tree planting at Quarry Farm, 1910s |

Dr. Booth was rightly proud of the results. He was one of the prominent speakers at the annual Forest, Fish and Game Association convention in Syracuse that December. His topic was “An Arbor Day Tree Planting in Chemung County.” He also ordered 5,000 more young white pines from the state nursery to be set out by the school children of Elmira the next Arbor Day.

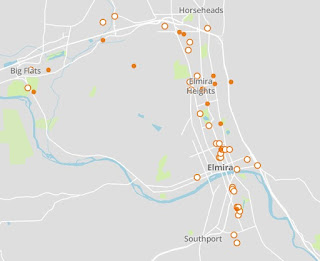

These tree plantings continued for the next few years. In addition to Quarry Farm, they expanded to other locations around Elmira including plots of land at the tuberculosis hospital on Underwood Avenue, near Bulkhead on the Southside, and by the reservoir on West Hill. In 1911, 30 grammar school girls joined the planting crew.

|

| Students planting trees northwest of Elmira, 1926 |

After 1913, reports in the newspaper become sporadic, so it’s unclear if the Arbor Day tree plantings had truly become a yearly tradition. On May 2, 1924, the Star-Gazette reported that a large delegation of seventh and eighth grade students attended the Arbor Day tree planting on East Hill. On May 3, 1934, some 15,000 trees were planted by public school children around Elmira. In that same article, the reporter expressed doubt that the custom would continue the following year. Over the previous two years, so many trees had been planted by paid workers as part of the Civil Works Administration (a New Deal program created during the Great Depression) that there wasn’t much clear land left for new trees.

|

Star-Gazette, May 4, 1934 |