by Erin Doane, Curator

The death of Miss Mabel Evans in Wellsburg was a great mystery. How did the beautiful young lady die, and why was she quietly buried at midnight? Thomas McGraw was sitting peacefully at home, thinking about Miss Evans when a strange impulse prompted him to rise and go to the door. Outside, he was astonished to see the graceful figure of a shrouded woman, floating through the darkness several feet above the ground. As he watched, she slowly drifted away and vanished into the night.

This was not Mr. McGraw’s first brush with the supernatural. His home just outside the southeast limits of Wellsburg next to the cemetery was a hotbed of paranormal activity in 1894. The two story house had a story-and-a half wing that had been closed up and unoccupied for years. Yet, two or three times a week for over four months, Mr. McGraw heard strange noises in the wing. Between 10pm and 2am, the sounds of distinct, measured knocking, muffled footsteps, and strange whisperings could be heard. Occasionally, there was a cacophony of sound that resembled the falling down stairs of a tray full of beer glasses accompanied by a bass drum and a barrel full of cymbals. Every time Mr. McGraw went to investigate the sounds, he found absolutely nothing amiss; not even the spider webs on the windows had been disturbed.

Word of the strange occurrences got around the small village, but no one was particularly surprised. Many residents had their own tales of deeds done by those who has long ago shuffled off this mortal coil. The stories managed to reach the ears of a reporter for the Elmira Telegram, and he was determined to investigate. While the reporter was never named in the subsequent article that described his experience, he did make it clear that he was a pronounced skeptic in matters pertaining to the spirit world when he put together the amateur crew of ghost hunters that would spend the night in Mr. McGaw’s haunted house.

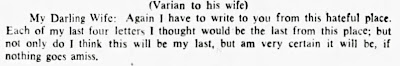

The newspaper man began his report of that night with the following: “Your emissary the other night had an attack of the horrors, felt his flesh creep and then stand in goose pimples, like the excrescences on the countenance of the tranquil cucumber, and all on account of an assignment to look up the story of an alleged haunted house in Wellsburg.” How did the avowed skeptic come to declare that “indisputable proofs of mysterious happenings in the realm of spooks have been furnished” after just one night?

|

| Elmira Telegram, November 18, 1894 |

Disappointed, but still hopeful, the ghost hunters decided that perhaps they were too early and that it would be best to go downtown for some time (to a pub or tavern, if I had to guess) and return later when the spirits were more likely to be abroad. While the crew and their hosts were at the undisclosed location downtown, those present shared blood-curdling stories about numerous murders, mysterious disappearances, and suicides that had taken place near the old church yard next to Mr. McGraw’s residence.

The investigators returned to the graveyard at midnight and “sat like five ghoulish figures” on headstones near the center of the burial ground. They “huddled shiveringly together, tried to smoke away the feeling of oppression, but in vain.” Suddenly, Mr. Pickley went pale. He slowly lifted his arm and pointed his finger to a spot not more than thirty feet away. The other men’s eyes followed his movement and they all plainly saw “a stately white robed figure…moving majestically along just above the toppling headstones.”

The five men rose from their hard, cold perches as one and gaped at the astonishing apparition. Without thinking, the reporter rushed toward the “beautiful gaseous figure.” Just before reaching it, the female figure turned its face toward him, rooting the hapless man to the spot. An indescribable feeling of oppression inspired by the awful spectral presence came over him and he fell face-first into the dead grass. The spirit turned away and dissolved into the darkness.

That vapory, filmy, relicts [sic] of those who once lived here on earth, do hover about us, and keep tabs on what we do or what we leave undone, is now [my] firm conviction.

– unnamed Elmira Telegram reporter, November 18, 1894