by Susan Zehnder, Education Director

Two years ago COVID-19 arrived, and since then we’ve all learned

to live with a variety of changes. One of those changes that continues to

evolve is how we present ourselves at work. With more meetings happening

remotely, some office workers are opting for a more casual look on the job but keep

“zoom shirts” or jackets handy to appear more presentable online.

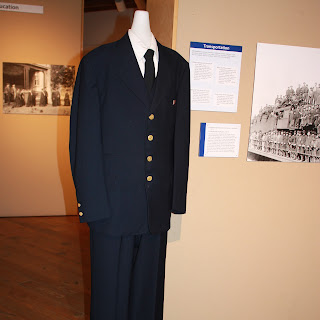

Our current exhibit All

in a Day’s Work: Dressed for Success shares examples of how, over the

years, different Chemung County professionals have dressed for work.

Three uniforms on display in our exhibit reflect some ongoing changes

in our societal expectations for work attire.

A woman’s nursing uniform, like other uniforms in the medical

profession, is designed to inspire patients’ confidence and trust. Being

attended by someone wearing a dirty uniform is almost hard to imagine, and the

importance of wearing a uniform in nursing can be traced back to Florence

Nightingale. When Nightingale established the world’s first secular nursing

school in 1860, she dressed her nurses in gray uniforms. The outfits helped identify

nurses who had training, and the gray didn’t show the color or blood when wet. The

uniform was also meant to neutralize the wearer’s appearance and deter

unwelcome advances from patients under their care, who were commonly young male

soldiers far from home.

At the beginning of the 20th century, nurses shifted

to wearing white. There were strict protocols and expectations for them to keep

their uniforms starched and pristine. Wearing white was “proof” that nurses

were clean, sanitary, and offered scientific care. Mid-century nurses wore

starched white dresses, white caps, white nylons and white shoes, similar to

the example on display from St. Joseph’s Hospital. Often nurses were required

to care for their own uniforms which meant time-consuming work to remove from

bodily fluids.

When women’s fashion became less restrictive, the style of

nursing uniforms followed along. By the 1970s and 80s, nurses began to wear

scrubs, and today scrubs are the primary outfit of choice for the profession

which includes more male nurses. Scrubs allow the wearer more freedom to move, often

come with pockets to carry tools, and can be worn by any gender. Scrubs come in

a variety of bright colors and patterns which allows nurses to personalize their

look, if their affiliated institution permits it.

For women entering the workforce during the last century, fashion

trends shifted from ultra-feminine to more traditionally masculine. Early on,

it was unthinkable for women in offices to show up without wearing stockings,

heels, skirts or dresses. Women began to wear suits similar to their male

colleagues, adding shoulder pads to convey power and authority. The office

worker’s outfit we have on display is a man’s suit from 1930, when white-collar

workers were expected to wear suits, hats, and dress shoes to the office every

day.

Today, advice for anyone interviewing for a job is often to

dress for the job level above the one they’re applying for. What we

choose to wear is a kind of language. We represent the organizations we work

for as well as representing ourselves, and our clothes can say something about

us.

Whether or not the more casual styles adopted during the pandemic

stay with us, we’ll just have to see.