By Rachel Dworkin, Archivist

Earlier in the year, I had a researcher who came every Friday for a month to look at our collection of reports of the Elmira Board of Health. I asked her what she was looking for. She explained that she was an ER nurse and was looking at historical records to see what the hospital might be in for if people stopped vaccinating their kids. “It’s going to be bad,” she said, looking over her notes. “It’s going to be really bad.”

At present, the State of New York requires that all students be vaccinated against measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, hepatitis B, and chickenpox in order to attend public schools (unless they have a medical exception). Additionally, students in grades 7 through 12 are required to have the meningococcal disease vaccine while kids in day care or pre-k must have haemophilus influenzae type b and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. Any one of these diseases can cause lasting debilitation or even death. Since the measles are in the news again after a series of deadly outbreaks, I’m going to focus on that one.

Measles is a highly-contagious disease which is spread through coughing, sneezing, etc. Symptoms include a high fever, cough, runny nose, inflamed eyes, white spots in the mouth called Koplik spots, and a red rash which spreads from face to feet. The symptoms appear within 10 to 12 days after exposure and usually last about a week. Common complications include diarrhea, ear infection, and pneumonia, but some unlucky sufferers can get inflammation of the brain resulting in seizures, blindness, and lasting brain damage. The virus causes patients’ immune systems to reset, making them susceptible to other illnesses, even ones they’ve already had, for several years after. Approximately 2.5 of every 1,000 modern cases results in death.

Looking at the historical record, measles was consistently the most common communicable illness in Chemung County. The exact numbers fluctuated from year to year. In 1925, there were just 49 reported cases in the City of Elmira. In 1949, there were 2,395 cases resulting in 2 deaths. In the days before antibiotics, patients were more likely to die of complications, especially pneumonia. In October 1869, an outbreak of measles at the Southern Tier Orphan’s Home resulted in 14 cases. Two children died. In an interview with the newspaper, the home’s matron said, “It is a comfort to think that these little ones, whose early life had been so darkly shadowed, are now safely gathered in a permanent Home, where sickness never enters, where want and orphanage are unknown, and where they may enjoy all the privileges of heirship in that beautiful land on equal footing with the children of wealth and nobility.”

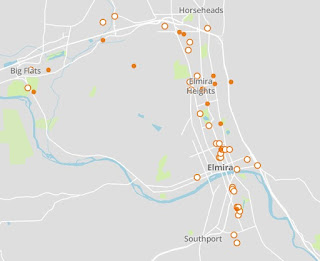

|

| Elmira Board of Health, Annual Report, 1949 |

When cases were reported to the local Board of Health, officials would placard and quarantine the homes of patients in hopes of stopping the spread. In June 1897, there was a bit of a mystery surrounding the removal of a health placard placed at the multi-family home at 604 East Water Street. Mrs. Martha Tuttle, originally of North Chemung, was renting rooms there so her 15-year-old son might attend Elmira Free Academy. When he contracted measles, the home was placarded and quarantined. Mrs. Tuttle took her son home to North Chemung to recover and someone at the house removed the sign so the other residents could go back to school and work. The removal of a health placard without the approval of the health department was technically a crime, but no one was ever charged. While it was rare for people to just remove signs, it was apparently not uncommon for people to not report cases so as to avoid being placarded in the first place.

|

| Elmira Gazette, June 30, 1897 |

The measles vaccine was first approved for use in the United States in 1963. There were subsequent improvements to the vaccine in 1968. A few years later in 1971, it was combined with vaccines for mumps and rubella to form the MMR vaccine. Children must receive two doses to be fully immunized. Thanks to the vaccine, measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000, but, since then, it has made a resurgence thanks to vaccine hesitancy among certain groups. According to the CDC, as of May 22, there were 1,046 confirmed cases of measles in 2025 across 31 states. 96% of those patients were unvaccinated, 12% required hospitalization, and three have died.

Knowledge of the past is essential for understanding the present. It’s also important for predicting possible future outcomes of our decisions. Most American’s Gen X and younger have never had measles, let alone known someone who died from it. And yet, a quick look at the historical record proves my researcher is right. Stopping vaccination will result in more infections and more death. The good news is, by arming ourselves with that knowledge, we still have time to make better choices.

.jpg)