by Susan Zehnder, Education Director

The 19th

century saw photography inspire a brand-new medium: moving pictures. By the end

of the century, most movies were 30 seconds or less, but they captivated

audiences who flocked to see them. New York City was the industry’s production center,

though there were few designated venues to show films. Most early movie venues

or “houses” were hastily improvised. Often located in immigrant and

working-class neighborhoods, movies were frequently shown in overcrowded rooms.

There was legitimate concern about fire safety. They also became associated

with illicit activities like gambling and prostitution. Social reformers

pressured the city’s mayor, George McLellan, to do something.

Mayor McLellan was the son

of the famous Civil War general and had first been elected at the age of 29. Near the end of his time in office, on Christmas Eve 1909, he

suddenly revoked all film exhibition licenses throughout the city. The order temporarily

shut down the movie business. His reasons were hazardous conditions (the celluloid

film sometimes spontaneously ignited) and the degradation of community morals. It

couldn’t have hurt that he had the backing of Broadway live theater

owners concerned with the new competition.

Movie exhibitors fought

back. Declaring their fight for freedom of speech, they formed the New York

Board of Motion Picture Censorship. Ironically, they soon found the word

‘censorship’ to be too politically charged and changed their name to the

National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. The organization is still around

today and continues to advocate for movies as a legitimate art form to be judged

on the same aesthetics as theater and literature.

Closing early venues didn’t

slow the movie business. By 1914, it was estimated that over sixteen million

people in the nation went to the movies every day. Elmira venues, which started

showing up around 1900, reported that six thousand people attended movies every

day but Sunday.

|

| Star-Gazette June 5, 1914 |

Movies started featuring speaking actors, a variety of sound effects, and multiple camera angles, adding to a heightened sense of realism. They were entertainment for anyone with a little extra money in their pocket, and a welcome escape during fraught times. However, concern for the medium’s immoral influence continued to grow. In 1915, the Supreme Court ruled that films didn’t fall under free speech protection. Immediately, chapters of moral advocacy groups popped up around the nation to protect their communities. Members of these organizations included political, civic and religious leaders who advocated for the protection of public morals, especially in youth aged 15-20.

To counter, the film

industry came up with its own guidelines. In 1930 industry executives established the Motion

Picture Production Code, commonly known as the Hays Code. Its strict moral

guidelines were written by a Catholic priest.

Popular movies in the 1930s

included Walt Disney’s first animated feature film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, at 88 minutes long, The Wizard of Oz, at 102 minutes, and Gone with the Wind, at a lengthy 222 minutes. However, communities continued to question the

industry.

What, if anything, was

going on in Elmira? In 1920 the local chapter of the Daughters of the American

Revolution (DAR) formed a motion picture committee to “promote a sentiment

toward securing and patronizing better films in Elmira.” One prominent member

of this group was Mrs. Charles (Lina) Swift. Swift was a practical nurse, art

teacher, fierce PTA advocate, and mother of four.

In November of that year, Swift spoke at a local PTA meeting, with over 200 parents in attendance. She told them about the “patriotic, historic and educational work” the DAR was doing. She wanted to share the DAR’s alignment with the national movement “to get rid of offensive, unwholesome pictures that are shown.” She wasn’t against movies, but wanted to see control of them, and wanted the PTA’s support.

Soon the DAR committee

spun off to be an active independent community group first called the Motion Picture

Community Council and later the Better Film Council. Swift was appointed

president. She spoke at local and national meetings. In Elmira, monthly meetings were well attended and often featured their own

entertainment. At one meeting in 1935, members performed a dramatization of

American history from the early days at Plymouth Colony to the present time.

Other meetings held private screenings and talks by local clergy and academics.

The council also endorsed movies they thought were proper.

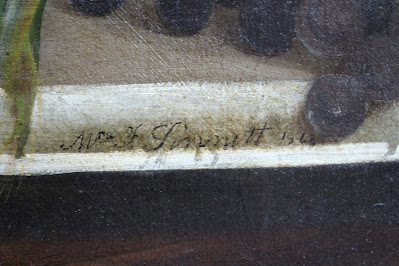

|

| (endorsement in lower right) |

Members of the committee traveled around the state speaking and encouraging other towns and cities to start their own film oversight committees. According to local newspapers, the council had the full support of Elmira area theater managers, who pledged to work with representatives of over 40 local organizations. No doubt theater managers didn’t want to lose any business.

|

| Colonial Movie House, Elmira. c. 1930s |

By end of the 1930s, the committee's work seems to have quieted down. No more activity from the Better Film Council appears in the local newspapers, and their movie endorsements ceased. Community attention must have turned to the rumblings of impending war.

In 1952, the Supreme Court ruled again. Movies were now protected by first amendment rights. Two years later, at 70 years of

age, Mrs. Swift died. She is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery.

.jpg)