By Rachel Dworkin, archivist

This past week, I was summoned for jury duty. These days, a lot of Americans would prefer to avoid it, but, historically, people have fought hard for the right to sit on a jury.

These days in New York State, potential jurors are drawn from lists of registered voters, local property tax payers, licensed drivers, and persons applying for public assistance. Once a pool of potential jurors has been summoned, the lawyers for both sides work together to select either six or 12 jurors (depending on the type of trial) and up to two alternates to hear the case. The attorneys interview potential jurors to select those which they think might be open to their case while excluding those they fear will not be. In an article entitled “How I Pick Out Men for a Jury” written for The American magazine in 1919, Elmira attorney John B. Stanchfield explained his process:

In selecting a jury, for example, the law plays practically no part. It is understanding of human beings that counts. For this reason, I study your face, your tone of voice, the answers you make and, especially, whether or not you look me in the eye when speaking. I make a point to find out whether you are well-to-do, or perhaps a clerk at a store. In addition, I always want to know the occupation of a prospective juror’s children, as well as the occupation of the juror himself. I ask your age, religion, and many other things because they all aid me, as the prosecutor or the lawyer for the defense, to make up my mind whether or not I want you for the jury.

Ideally, Stanchfield wrote, a jury should comprise of four strong men and eight intelligent and resolute ones. A juror who could empathize strongly with the defendant due to similarities in profession, class, religion, race, age, or club association, would be unlikely to convict, while someone from a different background might be more likely to return a guilty verdict. It was true back in 1919 and it is still true today. That’s a big part of why so many people have fought so hard to ensure that women and minorities can participate on juries.

|

| John B. Stanchfield, attorney |

The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution abolished slavery and guaranteed citizenship and basic civil rights to African Americans. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 explicitly extended those rights to include participation on juries, among other things. In 1883, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was overturned by the Supreme Court, opening the door for states to find ways of excluding Blacks from jury participation. This was especially the case in the South. In 1935, the Supreme Court reversed course in Norris v. Alabama (1935), declaring that the State could not systematically exclude Blacks from jury service. Individual lawyers could continue to attempt to dismiss potential jurors based on race until Batson v. Kentucky (1985), when the court ruled that a State violates a defendant’s right to equal protection in a trial where members of their own race have been purposely excluded from the jury. Despite the ruling, the problem of racial exclusion persists.

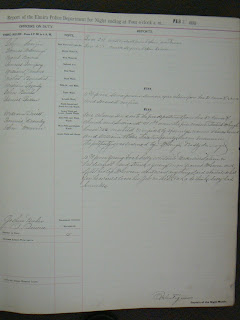

In Chemung County, only two Blacks were summoned as prospective jurors between 1875 and 1900. Richard Johnson, a Black man living on East Clinton Street, was summoned for a case in January 1899. He worked as a laborer and had not been following the news of the case in the paper, despite living in the same neighborhood as the victim. Attorney John B. Stanchfield argued that he was unqualified to serve and had him dismissed. It was not until well after 1935 that a Black man was selected to sit on a jury in Chemung County.

|

| Chemung County courtroom, 1896 |

Women were also long excluded from juries. In 1870, the Chief Justice of Wyoming Territory began the practice of mixed-gender juries, but his successor in 1871 terminated the practice. In 1883, Washington Territory granted women the right to serve on juries, but subsequently rescinded it in 1887. Utah became the first state, in 1898, to grant women the right to sit on juries. After New York women won the right to vote in 1917, a group of four women who had recently registered to vote became the first women to sit on a jury in this state in a case in Sidney in January 1918. The problem was, New York State law specified that only men could serve as jurors. It wasn’t until 1927, after repeated attempts to amend the law, that New York officially allowed for female jurors, but service for women did not become mandatory until 1930s.

In 1935, The Star-Gazette interviewed local women about their thoughts on compulsory jury duty for women. Dean Frances M. Burlingame of Elmira College was all in favor as she didn’t “see any essential difference between the citizenship of men and women” and therefore believed women should have the same duties as men. Others were somewhat less enthusiastic about the prospect of serving, but agreed it was important. Mrs. George Diven, president of the Chemung County Republican Women’s Club, disapproved of the entire jury system, but did not say what she would replace it with.

Mississippi became the last state to make women eligible for jury duty in 1968. As late as 1979, some states continued to require women to opt-in to serve until the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional. In 1994, the court ruled that a jury where members were excluded based on gender was a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

I didn't end up on a jury this time, but I'm still glad I at least have the right to serve.