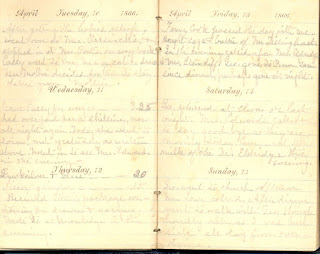

by Erin Doane, Curator

On February 2, 1933, WESG aired the first in a series of weekly musical radio programs sponsored by Standard Food Stores. Just nine weeks later, on April 7, an article in the Star-Gazette reported that dictionaries were suddenly in high demand at the Steele Memorial Library. “Legitimate” students were being crowded away from the library’s few available dictionaries as a direct result of this new radio show. How did this strange turn of events happen?

The perpetrator of the unexpected dictionary

shortage was Standard Food Stores. In 1929, grocers in Elmira, under

the guidance of C.M. and R. Thompkins, came together to form a group under the

name “Standard Food Stores.” Each member business in the group remained

independent but they worked together to give customers “better quality, better

service, and better prices.” Initially, it was just grocers within the city of

Elmira who were members of this group but it quickly grew to include stores

throughout Chemung County and northern Pennsylvania.

Postcard

showing the Steele Memorial Library, c. 1940s

As part of its promotional efforts, Standard Food

Stores started sponsoring a musical program on local radio station WESG in February 1933. For 15 minutes every Thursday morning

starting at 11:30, listeners were treated to the sounds of the Standard Food

Stores Orchestra under the direction of Don Huber. Also featured were Grocer

Boy with his flowing tenor and Grocer Girl with her pleasing voice who would

sing old time tunes. The duo was credited with much of the show’s popularity.

Fans said they made the program one of the best broadcasts of its kind on the

local station.

Standard

Food Stores Advertisement from the Star-Gazette,

May 23, 1929

Many listeners wanted to know who Grocer Boy and Grocer Girl actually were. The pairs’ identities remained a secret until early May when their names were finally revealed. Grocer Boy was Paul Huber, brother of the orchestra leader. He was a regular performer on WESG throughout the early 1930s and also involved in local minstrel shows.

Grocer Girl was 31-year-old Florence Rohan. Florence was a musical prodigy who started playing the piano before she was three years old. Around 1925 she started touring with her two young daughters Jacqueline and Marilynn as the vocal group the Lullaby Trio. The group’s heyday was in the late 1930s and early 1940s when they performed on several national radio program including NBC’s Children’s Hour, the Horn and Hardart Children’s Hour on CBS, and Major Bowes’ Amateur Hour. The Trio also performed numerous times in Florida and once on a cruise ship to Bermuda.

Florence had moved with her family to Elmira from Hornell in 1932 and quickly became a regular on WESG. She was particularly active on the Arctic League programs. She ended up being the first woman announcer on Elmira radio, writing and presenting her own programs as “the Rosenbaum Stylist.” At the time of her unexpected death in 1962, she was one of the region’s best known musicians and performers.

But what does all this have to do with the shortage of dictionaries? Well, I’m getting there. On March 30, 1933, a word-building contest was announced on Standard Food Stores’ weekly musical radio program. During the 1930s, word games and contests became quite popular. In one particular type of word-building game, a song title was given and people tried to make as many words from the letters in the title as possible. Those with the most words could win prizes. A large dictionary was a great tool for such a challenge. I don’t know the particular details of the WESG contest, but because of the large audience brought in by the song stylings of Grocer Girl and Grocer Boy, many people heard about the contest and got working on word-building.

Headline

from the Star-Gazette, April 7, 1933

By mid-summer, the run on dictionaries at the Steele Memorial Library slowed down. The series of entertainments on WESG featuring Grocer Girl, Grocer Boy, and the orchestra with the associated word contests came to an end on August 3, and a whole series of novelty broadcasts commenced under the sponsorship of Standard Food Stores.