by Susan Zehnder, Education Director

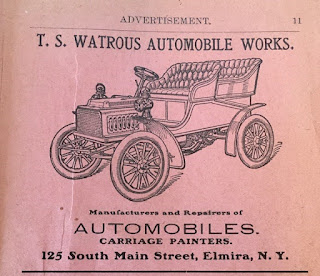

In 1904, Thomas S. Watrous founded the Watrous Automobile Company (WAC) on Main Street, hoping to cash in on the public’s growing desire for automobiles. The new industry was hot. The first American patent for a combustion engine had been filed twenty-five years earlier and now over 3,000 models were on the market. Each car was assembled by hand, making the median price around $1,000. However, the average yearly salary was only $200 - $400. For many the dream of owning their own automobile was still unattainable. Watrous wanted to offer customers more affordable options.

The first car purchased in the county was a Winton Roundabout six

years earlier. The buyer was a local doctor William H. Fisher, and the car was manufactured

by the Winton Motor Carriage Company, out of Cleveland, Ohio. It was summer

when the car finally arrived. The event was announced in the local newspaper and

a spontaneous parade was organized to celebrate its arrival. Winton automobiles

had a reputation for quality and durability. A few years later, a Winton

Roundabout would be driven across the country, successfully completing the nation’s

first transcontinental drive. Without connected roads or reliable maps, Dr. H.

Nelson of Vermont drove from coast to coast in under 90 days.

Fisher’s Roundabout engine had one cylinder and an advertised

speed of 20 mph, which he put to the test.

|

| Dr. Fisher and Dr. Carey in Fisher's Winton |

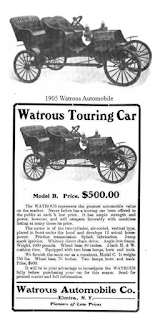

In the spring of 1904, when T.S. Watrous established the Watrous

Automobile Company, business headquarters were located at 125 S. Main Street,

Elmira, long gone today. His plan was to open a manufacturing plant on 11th

Street in Elmira Heights, where WAC would produce two affordable models: the Model

B, a Touring Car which would cost $500, and Model C, a Runabout which would cost

$400. This was half the cost of other car models at the time. In early 1906 WAC

was ready and advertised their vehicles widely. Orders soon rolled in.

To secure a vehicle, potential customers were asked to send cash deposits of $100 - $200. The company began producing inexpensive car parts, getting ready to assemble, but demand soon outstripped their capacity to deliver. Very quickly they gained an undesirable reputation. The Third Edition Standard Catalog of American Cars 1805 - 1942, a well-regarded catalog, reports the car was "...a noisy car, and a pretty awful one. Local wags dubbed it the waterless, gearless, powerless, useless Watrous.”

In March 1906, Hilliard Clutch & Machine Company moved

into the building occupied by WAC, and by summer WAC was out of business

completely. Watrous’s automotive dream was over. Previously, Watrous had been a

carriage painter and earlier notices in the newspapers had him claiming to be

the inventor of a “revolutionary” fruit preserving process that would change

the industry. When WAC folded, he returned to his earlier profession of

carriage painter for a few years, then in 1911, moved to Florida.

In the end, the Watrous Automobile Company assembled just one vehicle.

After the company folded, the car was sold to a client in Pittsburgh for the

sum of $300 in addition to a previously made deposit. It was reported in the

Star-Gazette on September 15, 1909, that according to its owner, this Watrous “worked

alright.”

This would be the only automobile ever produced in Elmira. Other

automotive companies associated with Elmira, like Willys-Morrow produced their

cars elsewhere. In 1908, Henry Ford manufactured his Model T in Michigan and created

a new kind of production model. He designed an assembly line and changed industry

standards and customer expectations. Manufacturers shifted from producing a small

number of handmade cars to producing millions. Ford’s approach brought the

price of automobiles down and within reach for more Americans.