By Rachel Dworkin

On May 18, 1944, Mr. and Mrs. John Wronkoski were elated to become new members of an exclusive club which met monthly at the German Evangelical Church under the auspices of the America Red Cross. Their son, Lt. Edward Wronkoski, had been shot down over North Africa and been reported missing on March 29th. They were understandably relieved to learn, nearly 2 months later, that he was alive and well in a German prisoner of war camp. The parents and wives of the Red Cross’s POW kin support group welcomed them with open arms.

During World War II, 100 Chemung County servicemen were held as prisoners of war. The majority were held by German forces, with just a handful held by the Japanese. Lt. Frederick F. Loomis, pilot with a bomber group in stationed in North Africa, was the first Chemung County man to be taken prisoner after being shot down on February 23, 1943. In his first letter home after his capture, received on April 28th, he assured his parents that he was fine and asked them to send candy, books, and model airplane kits to help relieve the boredom. His parents, Fred and Edythe Loomis, became the founding members of the Elmira Red Cross Prisoner of War Committee.

Over the course of the war, the American Red Cross delivered over 27 million food parcels to 1.4 million U.S. and allied POWs held by Germany. They did not send parcels to the Pacific theater as the Japanese refused to take delivery. Around 13,500 volunteers working at packing centers in New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, and St. Louis assembled 11-pound packages of non-perishable foods like dried fruits, canned meats, condensed milk, hard cheeses, crackers, jam, sugar, chocolate, and cigarettes. They also sent special packages with blankets, clothes, medical supplies, and toiletries. The turn-around from packing to delivery was about three months and the Red Cross tried to time it so that prisoners received a package a week.

Sgt. Henry Pickel of Southport, held captive from August 7, 1944 to January 31, 1945, claimed that the Red Cross packages made all the difference. “If it hadn’t been for the American Red Cross, the food situation would have been extremely serious,” he later told a reporter from the Star-Gazette. The Germans only fed them a slice of bread and a bowl of potato soup once a day, and prisoners relied on the weekly food shipments to stave off mal nutrition. That wasn’t all the Red Cross provided. “They sent us food, clothes, and warm blankets,” Pickel reported. “Until the blankets came, we had been trying to keep warm with small, worn out blankets that didn’t begin to do the job.”

| ||

| Sgt. Henry Pickel |

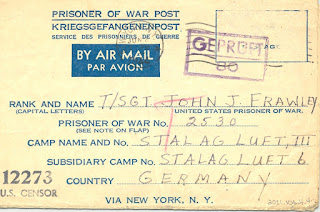

Prisoners’ friends and family could send packages too. In May 1944, the Loomis family sent their captive son four tiny screwdrivers and a pair of tweezers so he could do watch repairs. In another package, they sent him a saxophone. The Frawley family of Elmira sent their son, T-Sgt. John Jr., a package with cigarettes and a photo of the family dog. Despite being forced to march from camp to camp as the Allied armies advanced, John Frawley Jr. managed to hang onto every letter his family sent, along with the increasingly worn picture of Tippy the dog. Loomis, on the other hand, was forced to leave his belongings behind.

Photo John Frawley had of his dog

One of the things that the Elmira Red Cross Prisoner of War Committee did, in addition to providing emotional support, was to help teach the families of POWs how to ensure that their letters and packages actually made it to the prisoners. Packages could not weigh more than 11 pounds and had to be clearly labeled with the prisoner’s name, rank, prisoner of war number, and camp number. Each package and letter was reviewed and censored by the American government and read again and approved by the Germans before being passed on to the prisoners. By 1944, the U.S. government began issuing special stationary for mail to prisoners and only letters which had been typed or written in block capitals were accepted.

Stationery for letters to POWs

The captured men

and their families were all incredibly grateful to the Red Cross. While still

prisoners in Germany, Lt. Frederick F. Loomis and Lt. Edward Wronkoski both had

their parents donate $25 from their bank accounts to the Red Cross’s

fundraising drive in March 1945. Lt. John McNamara, who had been sent home as

part of a wounded prisoner exchange, also donated to the cause. After his

return of Elmira in April 1945, Sgt. Henry Pickel spoke before the Elmira Red

Cross Prisoner of War Committee, describing his captivity and thanking them for

their efforts.

No comments:

Post a Comment