By Rachel Dworkin, Archivist

At 3:30 am on the morning of October 7, 1864, a man emerged

from a hole on a side street by the northern fence of the Elmira Prison Camp. He

was Washington B. Traweek, a nineteen-year-old private from Alabama who had

been captured while serving with the Jeff Davis Artillery. There were Union

guards on patrol across the street, but they never noticed him as he snuck

along the fence before fleeing around a convenient corner. He was soon followed by nine other men, the

last emerging around 4:30 am. It was the single largest escape from the North’s

most secure prisoner-of-war camp.

The escape plot began on August 24th when John F.

Maull, John P. Putegnat, and Frank E. Saurine all swore a secret oath to dig

together. Traweek joined them almost immediately. The four men started digging

the tunnel from Maull and Putegnat’s tent located approximately 68 feet from

the camp’s northern stockade wall. The digging was exceptionally slow going so

they recruited six additional men, S. Cecrops Malone, Gilmer G. Jackson,

William H. Templin, J.P. Scruggs, Glen Shelton, and James W. Crawford, to help

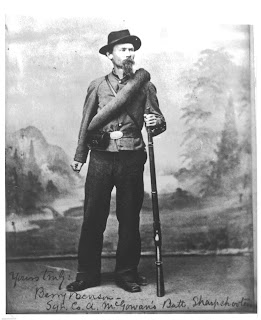

out. Berry Benson of South Carolina

joined the team in early September after he spotted Traweek disposing of rocks

from the tunnel and asked to be let in.

|

| Berry Benson in his old uniform after the war. |

The tunnel took months to dig. Two men would go down into the

tunnel where one man would dig with a pocket knife while another would load the

dirt into a bag made from a spare shirt. The team up top would unload the dirt

into their pockets to be disposed of later around camp and then send the bag

back down. Working in the tunnel was deeply unpleasant. In his memoir, Benson

said it was “next to death by suffocation to go into it.” The tunnel was so

narrow that the digger’s body blocked the flow of air leaving the digger sweltering

hot and struggling for oxygen. Diggers came up with racking headaches, dizziness,

and vomiting and needed to be relieved every 15 to 20 minutes.

|

| The bag used to move dirt with insets of John P. Putegnat during and after the war. |

In mid-September, Traweek and Putegnat dug a second tunnel

from the newly constructed hospital, this time with a spade. They made it to

the wall in just two nights but, before they could gather their friends to get

them out, the tunnel was discovered. Traweek was thrown in the camp’s jail and the

guards conducted a camp-wide search for additional tunnels. Twenty-eight were

discovered, but not the team’s tunnel which was concealed by a carefully

preserved chunk of turf held in place by a plank just below the surface.

Traweek was released from the camp jail in late September to

rejoin his fellows. By this time, Saurine had been kicked off the team for

refusing to dig. It turned out to be a bad decision on his part. All of the

tunnel conspirators made it out and away. Maull, Jackson, and Templin made

their way south together on foot, as did Traweek and Crawford. Somehow Malone and

Putegnat got turned around and ended up in Ithaca. They headed still further

north before taking jobs in Auburn and using their earnings to travel to

Baltimore by train and boat. Benson and Scuggs both made their own ways home alone

while Shelton seemingly dropped off the face of the earth.

The escape was discovered during roll call on the morning of

October 7th and threw the camp into an uproar. Guards frantically

searched the camp and surrounding area for the tunnel and missing men. Wild

rumors circulated among the prisoners. One prison diarist, Wilbur Grambling, wrote

that 25 men had escaped, each with a stolen horse.

|

| Morning roll call at the Elmira Prison Camp |

Although many others tried to replicate their feat, theirs was

the last successful tunnel escape at the camp. Seven other men managed to make their

way to freedom by various other methods. One smuggled himself out in a swill barrel.

Another stole a Union sergeant’s overcoat and strolled out the front gate

without being challenged. The most brazen escape was by a man named Buttons who

faked his own death and jumped out of a coffin on the way to the cemetery.