by Erin Doane,

Curator

While doing research

for the exhibit To the Rescue: Early

Firefighters in Elmira, I came across a note about a man called “Chief

Ross.” A file containing reminiscences of firefighters in the early 20th

century included the story of a local character who made daily rounds visiting

all the fire stations in the city. Chief Ross was described as “a simple,

trusting soul with a retarded mentality but a faithful desire to please

others.” He adored the firemen, lived meagerly, and died of pneumonia. His

funeral was attended by a platoon of off-duty firefighters in full uniform and

he was buried in the Exempt Firemen’s plot in Woodlawn Cemetery.

The short

reminiscence gave a very brief account of this man’s life but I wanted to know

more. In so many cases like this it is difficult, if not impossible, to find

more information. Imagine my surprise when I found a newspaper article about

Chief Ross and then a photograph of him as I continued my research in our

archives. An online search of newspapers uncovered a half dozen more articles.

While I still have a lot of questions about Chief Ross’s life and death, these

articles provided far more information than I had expected to find.

|

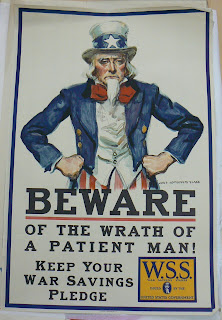

| "Chief Ross" wearing some of his many medals in 1907 |

Charles Owens was

Chief Ross’s actual name. In 1926, Elmira fire chief John H. Espey told the Star-Gazette how Owens had come to be

known as “Chief Ross.” “The only way I can figure it out is that Owen greatly

resembled the lost Charley Ross, kidnapped in the ‘70s and never found. Although never a

fireman, he bossed the department and told the boys just what to do, and when

they didn’t do it, he threw off his coat and entered the thick of the fight

with them. So they called him Chief Ross and the name stuck.”

Chief Ross started

following the activities of the Elmira fire department at an early age. He

visited the stations regularly and helped out whenever he could at the stations

and at the scenes of fires. During the Lyceum Theater fire on March 8, 1904,

which burned most of a block on Lake Street between Carroll and Market Streets,

he hurried to assist the firefighters when asked while other men simply stood

and watched. A newspaper report about the fire declared that Chief Ross was “a

rough sort of fellow and possibly don’t know why it is that radium cures

cancer, but he has just enough of that fool-hardy valor to make him of much use

on such occasions.”

In another instance,

when the department was still using horse-drawn equipment, Chief Ross stepped

in to lend a hand. It was a cold winter night and three homes were on fire. The

driver of one of the engines could not manages the horse so Chief Ross took the

reins. He was able to calm the rearing horse and got the engine to the fire in

record time. When he drove through Eldridge Park on the way, the horses were

going so fast that they could not be slowed down to go under the railroad.

Thinking quickly, he turned them and ran around the lake instead.

While Chief Ross

never took a salary as a firefighter, he was a fixture in the department. He

was at nearly every fire in the city and had a wonderfully retentive memory for

facts and figures related to the conflagrations. Over the years, he also

amassed a remarkable collection of firefighting badges, medals, and pins which

he wore on a vest. One particularly large badge was made from the boiler plate

of a steamer fire engine. It was reported that he wore his “18 pounds of

medals” when he attended the firemen’s convention at Hornell in July 1909. The Star-Gazette reported that “‘Chief Ross’

will be one of the characters of the convention. He expects to open the new

fire station and expects that he will be the grand marshal of the parade. He

will also, he expects, respond to the address of welcome and will bow to the

right and left when a chorus of 600 children sing ‘We Welcome You, O Chief.’”

Newspaper articles

about the “Chief” were often written in a playful, or one may say, patronizing

tone. For example, when he was found drunk at West Church and Davis Streets in

April 1916, it was reported that “he was arrested for having taken on too big a

cargo of fire water.” He appeared before the judge wearing a “big badge, the

gift of No. 5 station firemen” and his sentence was suspended. While most

people, including the firefighters and reporters, were quite fond of

Chief Ross, it seemed that others would put him down and picked on him because

of his lower mental capacity. During the Lyceum Fire mentioned before, the

reporter noticed that among the gathered crowd of onlookers “there were a lot

of men and boys who were doing all they could to amuse themselves at the

chief’s expense.” Even the firefighters themselves would sometimes make him the

butt of their jokes. In the original reminiscence that introduced me to Chief

Ross, a firefighter stated that they were not unkind to him but they

“would have a little fun” with him at times.

In June 1926, while

visiting fire station No. 2, Chief Ross fell ill. The firefighters helped him

to the bunk room to rest but he got worse. They then took him to the hospital

and found that he had a severe case of pneumonia. On June 21, he died at the

county farm in Breesport. The firefighters immediately started a fund to raise

money for a fitting burial. Chief Espey, Commissioner Leonard Whittier, George

Remer, and nearly every off-duty firefighter in the city attended the funeral

while six firemen served as pallbearers. After devoting nearly 45 years of his

life to the Elmira Fire Department, Chief Ross, Charles Owens, was laid to rest

in the Elmira Exempt Fire Association’s plot in Woodlawn Cemetery. His headstone

is inscribed: Member of Paid Department.

|

| Elmira Exempt Fire Association plot in Woodlawn Cemetery |